A B S T R A C T

Symptoms of vicarious trauma, coping strategies, and prevention suggestions were investigated with 105 judges. Participants completed a self-report measure developed for this study. The majority of judges reported one or more symptoms that they identified as workrelated vicarious trauma experiences. Female judges reported more symptoms, as did judges with seven or more years of experience. In addition, female judges were more likely to report internalizing difficulties, while judges with more experience reported higher levels of externalizing/hostility symptoms. Coping and prevention strategies were multi-domain (i.e., personal, professional, and societal) and underscored the need for greater awareness and support for judges.

Fall 2003, Juvenile and Family Court Journal

Becoming a judge is considered the pinnacle of one’s professional achievement in the field of law. Literally and symbolically, judges are the face of justice in many aspects of their community. Judges must model fairness, impartiality, patience, dignity, and courtesy to all with whom they come in contact, in contrast to the often rough-and-tumble environment that constitutes the courtroom. Matters of domestic violence, murder, rape, child neglect and abuse, divorce and child custody, mental illness, sentencing, and more play out daily, while the media, families of the parties, victims, and others often observe and comment. The combination of factual circumstances and emotions that are displayed, together with the sheer volume of cases, would test any judge’s patience.

As modern-day judges take the bench, we need to ask what skills, values, and attitudes they need to bring with them and to develop as they continue their careers. How can they balance the need to be human and engaged in their work with the need to maintain professional distance? Is their role that much different from an emergency room physician, clergy person, mental health professional, or social worker? And what models and techniques exist to guide judges in addressing the stresses and pressures of daily emotion-laden cases? A better appreciation of all of these dynamics helps inform the judiciary to remain as effective as possible in the face of these stressors. At the extreme, these stressors, together with the traumatic nature of the material that judges have to consider, can result in vicarious trauma.

What is Vicarious Trauma?

Vicarious trauma (VT) refers to the experience of a helping professional personally developing and reporting their own trauma symptoms as a result of responding to victims of trauma.VT is a very personal response to the work such helping professionals do.VT is sometimes used interchangeably with terms such as compassion fatigue, secondary trauma, or insidious trauma. This phenomenon is most often related to the experience of being exposed to stories of cruel and inhumane acts perpetrated by and toward people in our society (Richardson, 2001).The symptoms of VT parallel those of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and can be similarly clustered into the areas of re-experiencing, avoidance and numbing, and persistent arousal (Figley, 1996a). The fundamental difference between VT and PTSD relates to the nature of the stressor. Figley (1996b) distinguishes between these as primary (e.g., experiencing a serious threat to self or sudden destruction of one’s environs) versus secondary stressors (e.g., experiencing a serious threat to a traumatized person or sudden destruction of a traumatized person’s environs). Empathy has been identified as one of the mechanisms of transfer between primary and secondary trauma. Thus, the empathy that is so critical to working with traumatized people also increases the likelihood of vicarious traumatization.

VT has been identified as a potential occupational hazard for numerous professionals who confront trauma, violence, and personal injury.Although most of the research and literature has been geared toward police, therapists, shelter workers, and emergency relief workers, recent efforts have expanded the concept to recognize the risk of VT to those in other roles. Saakvitne and Pearlman (1996) offer a list of 21 professions that are affected by VT, and have expanded the traditional group to include others such as foster parents and prison staff. Although judges are also on that list (number 20 of 21), there has been little public recognition of VT among the judiciary until recently. Psychologist Isaiah Zimmerman conducted interviews with 56 Canadian judges and presented his findings at the Canadian Bar Association Annual Meeting in August 2002. His stories of the “torment” judges experience in dealing with cases of sexual abuse, child maltreatment, and domestic violence captured the attention of the public at large (Zimmerman, 2002; Makin, 2002). This article was written to extend this preliminary effort by Dr.Zimmerman and to serve as a springboard for future research and discussion in this area. We also recognize that there are many well-adjusted judges who truly enjoy their work and look forward to long and satisfying careers. The extent to which respondents in the Zimmerman study are representative of the general population of judges is unclear. Research in this area needs to be informed by judges who have developed successful coping strategies, as well as by those judges who have been more adversely affected.

An important conceptual distinction must be made between burnout and vicarious trauma.The construct of burnout has been the focus of far more theoretical and empirical study than VT (Jenkins & Baird,2002).Maslach (1982) developed the most widely used definition of burn-out: “A pattern of emotional overload and subsequent emotional exhaustion is at the heart of the burnout syndrome. A person gets overly involved emotionally, overextends himself or herself, and feels overwhelmed by the emotional demands imposed by other people” (p. 3).

Farber (1991) offers a slightly different definition, which posits burnout as a syndrome that stems from a perceived discrepancy between an individual’s effort in his or her work and the reward received for that work. Both of these definitions suggest that burnout can be a chronic, negative emotional experience, but one that lacks the intensity and trauma-related symptoms of VT. Thus, although burnout is neither necessary nor sufficient to produce VT symptoms, it can be a contributing or exacerbating factor. Burnout results in a vulnerability to VT, whereby the individual may not have the personal resources to combat the impact of VT effectively. Although stress may be normal and even motivational, excessive stress leading to burnout would likely magnify the impact of VT.

There are three overlapping spheres of experience that are thought to influence a person’s vulnerability to vicarious trauma: individual factors, organizational factors, and life situation factors (Saakvitne & Pearlman, 1996).The likelihood of experiencing VT is assumed to be related to the unique characteristics of individuals and their circumstances. For example, a judge dealing with domestic violence in a child custody hearing would more likely experience VT if he or she had grown up with domestic violence, experienced a recent or particularly difficult divorce, or had a heavy docket of these cases with little support from peers. Conversely, some judges may be better equipped to deal with difficult cases by virtue of their own life experiences including family, school, and work, while others who have been overly sheltered may be quite ill-prepared.

VT is especially relevant for judges given the changing nature of the cases in family, criminal, and civil dockets. Today we certainly hear more about and see more difficult cases including child abuse and domestic violence. There is also a clear trend toward unified or coordinated family courts and dedicated specialty courts such as drug courts, domestic violence courts, problem-solving courts, and community courts. The necessary corollary for judges in these courts is a steady diet of highly emotional cases. Judges’ dockets have changed dramatically in a short period of time and will continue to change as society tries to hold itself accountable for families, children, and communities in distress by placing more and more responsibility on the judiciary.

In some respects, the delay in recognizing judges’ vulnerability to VT may stem from several apparent contradictions. On one hand, judges may not be considered “front-line” workers in the same sense as child protection and shelter staff; on the other hand, judges are increasingly exposed to graphic medical evidence, tapes of 911 calls, photographs and videotapes of injuries, victim impact statements, victim testimony at trial and sentencing, and statements of surviving family members.

While judges are widely seen to occupy a place of privilege, the “privilege” of adjudication is often accompanied by isolation. In addition, there are many unique aspects to the judicial role that further complicate the process. For example, judges are required to maintain neutrality in the face of apparent tragedies and are expected to perform their duties impartially without being swayed by emotion. Judges are expected to keep their own counsel in the interests of confidentiality and due process.As a result, they are largely excluded from the critical debriefing process that is in place for many other front-line professionals.A number of recent initiatives have emerged to remedy this gap,including judicial mentoring programs and judicial teams that encourage collegial collaboration and debriefing.

The legal training that provides a foundation for judges’ careers emphasizes a variety of experience including trial preparation and advocacy, settlement and mediation, legal and factual analysis, working with expert witnesses, and legal research. Professionals in other sectors that deal with violence, such as social workers, may be better trained to disclose their own thoughts and feelings and to process the emotional impact of their work with their colleagues. Clearly, the judicial role is one that shares many characteristics with other professions that are recognized to create risk for VT, but also carries its own unique risk factors.

CURRENT STUDY

The current study was conducted as a preliminary investigation into the types of VT symptoms that judges experience over time. Because of the dearth of research in this field, the initial research questions were:

1. What are the rates and types of VT symptoms experienced by judges?

2. Are there relationships between VT experiences and judge characteristics such as age, experience, and gender?

3. What do judges suggest as effective coping and prevention strategies to deal with VT?

Method

Participants

A total of 105 judges were involved in the study (54.3% male,45.7% female).The average age of the judges was 51 years (SD = 8.1 years), with male judges significantly older than female judges, F (1, 103) = 12.69, p < .01. The average experience of the judges was 10 years (SD = 6.7 years), with male judges serving longer on the bench than female judges, F (1, 103) = 5.77, p < .05. With respect to type of court,81% did some criminal court work, 54% indicated domestic relations/civil court work, and 30% did juvenile court. (Percentages exceed 100% as a result of overlapping assignments.)

Materials and Procedures

Participants were judges attending one of four workshops. Three were entitled “Enhancing Judicial Skills in Domestic Violence Cases” organized by the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges and the Family Violence Prevention Fund,and the fourth was hosted by the American Judges Association on the topic of domestic violence. These conferences were held in Seattle,San Diego,Santa Fe, andMaui. These judges represent a cross-section of urban and rural centers across the United States, different levels of court, and a range of criminal, civil, and specialized courts.

Judges were invited to complete a survey that was distributed at a presentation on stress, burnout, and vicarious trauma.The survey asked questions about the short- and long-term impact of their job with respect to trauma symptoms, as well as coping skills and ideas about prevention.The sections on trauma symptoms and prevention strategies were open-ended. In contrast, the section on coping provided a list of possible activities that judges could identify, as well as a space to record additional answers. A copy of the questionnaire is available from the first author.

RESULTS

The results are organized into three sections: trauma symptoms, coping strategies, and prevention strategies.

Reported Trauma Symptoms

Overall, 63% of the judges reported experiencing one or more short- or long-term VT symptoms. Female judges were significantly more likely than male judges (73% vs. 54%) to report the presence of one or more symptoms (1, N = 104) = 3.83, p < .05. In addition, female judges reported more symptoms on average, F (1, 103) = 4.96, p < .05. When judge experience and trauma symptoms were inspected, there appeared to be a split around the seven year mark. Judges were categorized on the basis of having between zero and six years of experience (n = 38) or seven or more years of experience (n = 67). Judges with greater than six years of experience were more likely to report the presence of one or more symptoms (1, N = 104) = 6.11, p < .05. Judges with more experience also reported a significantly greater number of symptoms than those with less experience, F (1, 103) = 6.56, p < .05.

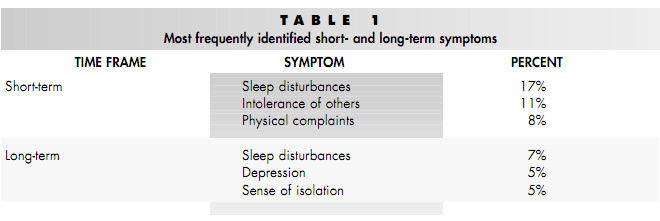

Because of the open-ended nature of the questionnaire, symptoms were coded into 39 categories that were developed for this study. These categories spanned a wide range of functioning, including interpersonal difficulties (e.g., lack of empathy, intolerance of others); emotional distress (e.g., depression, sense of isolateion); physical symptoms (e.g., difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite); cognitive symptoms (e.g., difficulty concentrating); and actual diagnoses (e.g., Major Depressive Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder). The most frequently identified short- and long-term symptoms are listed in Table 1.

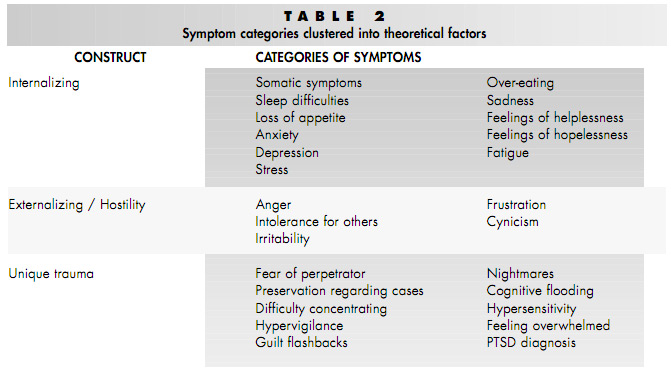

Next,the categories were further grouped into three symptom factors (i.e., internalizing problems, externalizing problems/hostility, and trauma-unique symptoms) on theoretical grounds as shown in Table 2. Short- and long term symptoms were combined for subsequent analyses. Internalizing symptoms were intended to capture those related to anxiety, depression, and somatic problems. Externalizing/hostility included strong negative emotions (e.g., anger, frustration, cynicism), and interpersonal difficulties. The unique trauma factor was constructed by mapping symptoms of VT onto the three domains of PTSD symptomatology (i.e., re-experiencing trauma event, avoidance/numbing, and persistent arousal) as posited by Figley in his seminal work (Figley, 1996b). Total construct scores were generated on the basis of these theoretical groupings, and judges were compared on the basis of sex and experience.

Female judges scored higher on the internalizing factor than male judges did, F (1, 103) = 4.32, p < .05, but there were no sex differences on the externalizing/hostility or unique trauma factors. Conversely, judges with seven or more years of experience scored significantly higher on the externalizing/hostility factor than those with less than seven years of experience, F (1, 103) = 6.88, p < .01). Judges did not differ on unique trauma scores on the basis of experience, but scores on the internalizing factor approached statistical significance, with more experienced judges reporting higher scores.

Coping Strategies

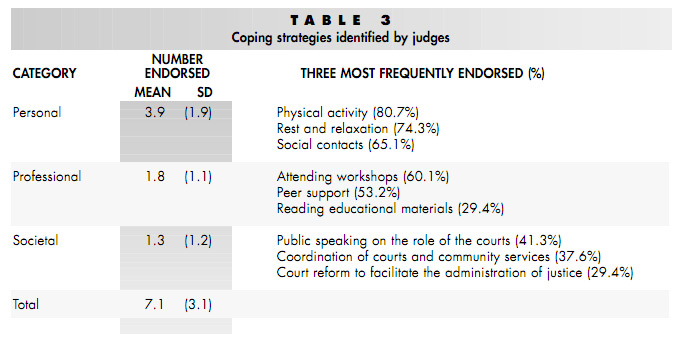

Judges were asked to identify coping strategies that they use to manage VT symptoms. Coping strategies were divided into three categories: personal, professional, and societal. The average number of strategies in each category, as well as the most frequently endorsed strategies, is shown in Table 3. There were no significant sex differences with respect to the number of strategies endorsed. Similarly, male and female judges were equally likely to identify any one particular strategy as helpful. Although strategies from all three domains of coping strategies were chosen, the majority of selected strategies were in the personal coping domain.

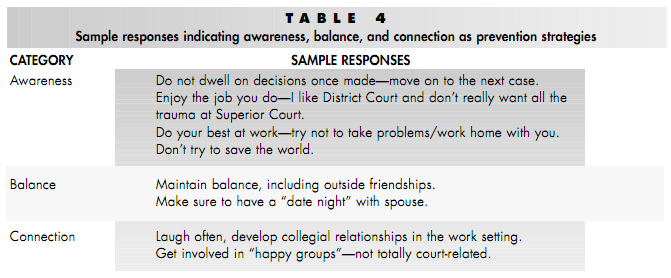

The Prevention portion of the survey provided an open-ended question for judges to identify potential strategies. Of the 105 judges, 73% provided at least one prevention strategy. These strategies included achieving balance between work and home life, developing healthy philosophies, and maintaining a sense of humor. The strategies were consistent with the ABC model of VT, which identifies three areas of intervention (Saakvitne & Pearlman, 1996). The ABC model identifies the importance of Awareness (i.e., being attuned to one’s needs, limits, emotions, and resources), Balance (i.e., among activities, especially work, play, and rest), and Connection (to oneself, others, and to something larger) (Saakvitne & Pearlman, 1996). Sample responses for all three areas are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to begin to document the VT experiences of judges. Although this was a preliminary investigation, the results indicate that judges do, unequivocally, experience trauma symptoms with respect to their work. The surveyed judges indicated a wide range of symptoms that they identified as stemming from their work, including cognitive (e.g., lack of concentration), emotional (e.g., anger, anxiety), physiological (e.g., fatigue, loss of appetite), PTSD (e.g., flashbacks), spiritual (e.g., losing faith in God or humanity), and interpersonal (e.g., lack of empathy, sense of isolation from others) symptoms. Clearly, judges’ exposure to the graphic evidence of human potential for cruelty exacts a high personal cost.

Additional findings from this study suggest that age, sex, and experience may be important factors in predicting judges’ experiences of VT. Furthermore, the respondents identified the importance of a range of coping strategies, and generated numerous prevention possibilities. Both the coping strategies and suggestions for prevention were consistent with previous work in the area of VT in that they highlight the importance of awareness, balance, and connection across both personal and professional realms of experience (Saakvitne & Pearlman, 1996).

One of the starkest contrasts arising from this research is the disconnect between what judges identify as ideal coping and prevention strategies and the reality of the judicial culture. While many of the judges surveyed indicated the importance of social support and debriefing, the reality is that some judges “work in isolation, they cannot consult about a case, they see horrific crimes, make weighty decisions and have to keep their mouths shut about everything” (Zimmerman, 2002, Makin, 2002, p.1). While we do not want to overstate the problem, isolation is indeed a dynamic that can and must be addressed, consistent with judicial ethics. The importance of debriefing and consultation are identified by mental health professionals as priorities for minimizing VT (Everly, Boyle, & Lating, 1999; Richardson, 2001; Saakvitne & Pearlman, 1996); unfortunately, because of the sensitive and confidential nature of the information handled by judges, these options are not readily available. As one judge was quoted in Zimmerman’s study, “I wasn’t prepared for the isolation of this position. It slowly overtakes you, and then you realize how alone you are, despite your friends and family,” (Zimmerman, 2002; Makin, 2002, p.1). Some judges have written about the unique opportunities to learn from tragedies rather than isolate themselves, through vehicles such as “Domestic Violence Death Review Committees” that address broader community and court responses that may prevent domestic homicides (e.g., Websdale, Town, & Johnson, 1999).

Another significant point of conflict between judges’ needs and the prevailing judicial culture relates to workload. In reporting coping and prevention strategies, many judges commented on the need for balance and putting boundaries around the work day. Some spoke of the need to be away from the office by a certain time, and others mentioned a more general need for balance between “work and play.” At the same time, many of the judges in our sample identified the increasing pressure to handle quickly or dispose of more and more cases by decision or settlement. The overwhelming workload of judges also emerged in Zimmerman’s study. He quoted one judge: “The sheer volume of each day’s work makes me fear I’m just processing people and have lost touch with my better self. Am I becoming indifferent to horror?” (Zimmerman, 2002; Makin, 2002, p.1). Thus, some of the characteristics that may define the experience of being a judge, particularly in jurisdictions without systemic controls (i.e., massive dockets, isolation, inability to debrief) are those same factors that have been identified as risk factors for vicarious trauma. On the other hand, some judges report the benefits of good administrative supports, which may be more apparent in a specialized court with judicial officers and court staff who are highly committed to their innovative endeavors (e.g., Town, 2001).

What are the Limitations of the Study?

Although this study represents an important first step in the investigation of VT among judges, there were several limitations with the research design. First, the sample was not random. All of the participants were attending a professional development workshop, which in and of itself has been identified as a prevention strategy. Second, the questions about symptoms were asked in an open-ended manner (rather than a checklist form). This strategy was appropriate given the exploratory nature of the study; however, it relies on a certain amount of personal insight. For example, if an individual does not make the connection between work-related stressors and interpersonal difficulties, then he or she will not provide that as an example of a VT symptom. However, that same individual might recognize the link if “interpersonal difficulties” were listed as one of several possible VT symptoms. As a result of the open-ended nature of this survey, interpretations about base rates of particular symptoms must be made very cautiously.

Future research in this area could expand in several ways. First, this preliminary pilot information could be used to generate a checklist of symptoms for a more structured assessment tool. The development of this type of tool would result in more accurate base rates of specific symptoms in future research. In addition, there is a need to collect more data about the nature of the judge’s workload and the nature of the court. From our experience training judges, those who specialize tend to have fewer symptoms, most likely owing in part to more resources, more intensive training, and more connection with the community. Another research direction would be to adapt existing models of VT to judges. In order to develop these models, information about childhood or adult experiences of abuse, current life stressors, and personal support networks would need to be collected, consistent with the emphasis on individual, organizational, and life situation factors Another key issue relates to the differentiation between ordinary levels of work stress, burnout, and VT. Longitudinal data collection with a larger sample of judges would facilitate this model building. As well, it will be important to understand better the process that leads to VT over time, in the same way that some authors have identified the stages of burnout, in order to promote early identification and intervention (Farber, 1991).To quote Ralph Waldo Emerson, “the moment we indulge our affections, the earth is metamorphosed . . . all tragedies, all ennuis vanish” (Emerson, 1993, p. 109-110). In other words, the key to prevention for many judges in this process leading to burnout and VT is staying engaged in their work (e.g., Town, 2001).

Finally, the meaning of gender differences in experiences of VT needs to be investigated further.It may be that female judges experience more distress, parallel to elevated rates of anxiety, and mood disorder in general as compared to males (APA, 2000). However, the extent to which this is a real difference versus one in reporting needs to be addressed. In a workshop on this topic, one of the authors (JudgeTown) found that individual judges greatly underestimated the impact of their stress and work on their personal functioning, compared with the stresses and changes noticed by their spouses. The participants were administered a standardized self-report inventory on stress, which provided the judges with feedback that suggested that they saw themselves under significantly less stress than reported by their spouses. This feedback generated some positive insights and commitments to change among the judges. Some of the respondents in this study noted that they had not been aware of the profound impact of their work until after they changed assignments and were able to gain more perspective. Research that includes other key informants in the data collection process will help disentangle this issue.

What Conclusions can be Drawn?

This study highlights the need for greater awareness about the experience of VT on judges and their capacity to meet the demands of their complex role in society. Future research needs to clearly identify the process by which VT emerges, together with related phenomena such as burnout. This exploratory study adds to the growing domain of VT research in other professions and draws attention to the multidimensional nature of the experience. The extent to which the prevailing theoretical model (which emphasizes individual, occupational, and organizational contributors to VT) applies to the experience of judges requires further study. In any event, our preliminary data should call attention to the significant number of judges who are profoundly affected by the nature of their work. There is an immediate need for broader discussions of VT in judicial circles and consideration of prevention and intervention strategies. Addressing this critical issue will allow the judiciary to continue to conduct its essential business with the concomitant public trust and confidence it deserves.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision.Arlington,VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Emerson, R.W. (1993) Essay VI: Friendship, in Essays, First and Second Series, 109-110 Gramercy. Originally published in 1841.

Everly, G. S., Boyle, S. H., & Lating, J. M. (1999).The effectiveness of psychological debriefing with vicarious trauma: A meta analysis. Stress Medicine, 15, 229-233.

Farber, B.A. (1991). Crisis in education: Stress and burnout in the American teacher.San Francisco,CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Figley, C. R. (1996a). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In Figley, C. (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized.New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Figley, C. R. (Ed.) (1996b). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized.New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Jenkins, S. R. & Baird, S. (2002). Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma: A validational study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15, 423-432.

Makin, K. (2002, Aug. 14). Judges live in torment, study finds. The Globe & Mail, 1.

Maslach, C. (1982). Burn-out: The cost of caring.EnglewoodCliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Richardson, J. I. (2001). Guidebook on vicarious trauma: Recommended solutions for anti-violence workers.Ottawa,ON: HealthCanada.

Saakvitne, K. W. & Pearlman, L. A. (1996). Transforming the pain: A workbook on Vicarious Traumatization.New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Town, M.A. (2001).The Unified Family Court: Preventive, therapeutic and restorative justice for America’s families and children.ABAChild Law Practice. Spring 2001.Washington, DC: American Bar Association.

Websdale, N. S.,Town, M.A., & Johnson, B. R. (1999). Domestic violence fatality reviews: From a culture of blame to a culture of safety. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 50 (2): 61-74.Reno,NV: National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges.

Zimmerman,I.(2002). Trauma and judges. Presentation to the Canadian Bar Association Annual Meeting, August 13,London,ON,Canada

________________

Peter Jaffe, Ph.D., C.Psych., is the Founding Director for the Centre for Children and Families in the Justice System of the London Family Court Clinic (1975-2001) and a Special Advisor on Violence Prevention for the Centre. He is a member of the Clinical Adjunct Faculty for the Department of Psychology and Professor (part time) for the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario, Canada.

Claire Crooks, Ph.D., C.Psych., is a Clinical Research Scientist at the University of Western Ontario Centre for Research on Violence Against Women and Children and an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Psychology. Dr. Crooks is co-author of a manual for a treatment program for abusive fathers, which is being piloted in London, Toronto, and Boston. She also conducts custody and access assessments through the London Family Court Clinic.

Billie Lee Dunford-Jackson, J.D., is the Assistant Director of the Family Violence Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Before coming to the Council, she practiced law for 16 years, with a specialty in family law. Her concentration at the National Council is on cutting-edge domestic violence issues, particularly regarding child custody and visitation, and on judicial education in domestic violence.

Judge Michael Town is a Circuit Court Judge for the First Circuit Court in Honolulu, Hawaii. He has been a trial judge since 1979, serving in family and criminal court. He was the presiding judge of the Honolulu unified family court from 1994 to 1997 and writes and speaks on preventive, therapeutic, and restorative justice.isitation, and on judicial education in domestic violence. Judge Michael Town is a Circuit Court Judge for the First Circuit Court in Honolulu, Hawaii. He has been a trial judge since 1979, serving in family and criminal court. He was the presiding judge of the Honolulu unified family court from 1994 to 1997 and writes and speaks on preventive, therapeutic, and restorative justice.